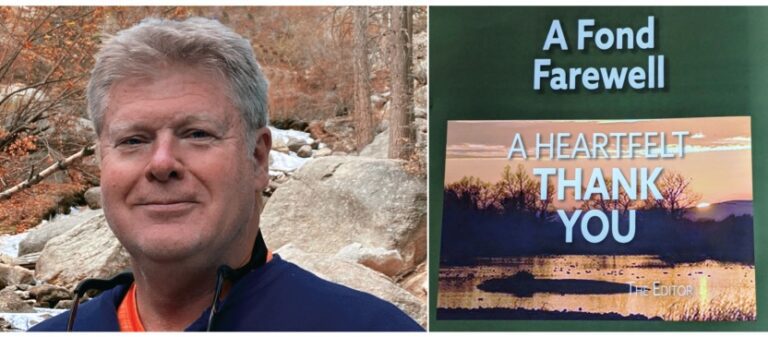

by Troy Swauger, Editor, Outdoor California

The other day I was looking at one of those mirrors that says, “Objects are Closer than They Appear.” I’m feeling like the message was directed to me because a lot of things are coming up fast and there’s no way to stop them.

I started with the State of California in 1996. In my relative youth, the only thing I focused on was achieving the next level, the next goal. After a couple years working where I was, I had a chance to move over to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and I took it. I’ve told this story before, about how my mom before she passed away was an avid angler and a veteran hunter. I know she would’ve been proud of me working for the organization that manages wildlife. And I enjoyed it, spending more than a decade as an information officer before I took over Outdoor California in 2008. After that, all my goals revolved around getting the magazine out under its two-month deadline. My awareness of time formed into the publishing dates of January/February, March/April and so on. I’ve never felt a need to give the end game much thought.

The longer I’m with the Department, the more grateful I am. I’m thankful for the life I’ve lived and the life I’m still living. In the decades that I have known here, there has been so much offered. The people are exceptional, the direction is clear, the pursuit is noble. The Department’s focus is spelled out in its mission statement: To manage California’s diverse fish, wildlife, and plant resources, and the habitats upon which they depend, for their ecological values and for their use and enjoyment by the public. Our path is guided by those who care greatly for this state, its wild animals and its natural beauty. It feels special to be counted amongst these people.

Let me tell you about the people who have the right to wear the Department’s blue and gold shoulder patch. It amazes me the work they do, and how much of it goes unseen. That’s what I always thought Outdoor California was for, to shine a light on CDFW and tell the world—one story at a time. The men and women who do these jobs are some of the most dedicated professionals I’ve ever met. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard them declare they have the best job in the world.

They’re wrong of course. I have the best job.

In the early years, I never thought of Outdoor California as my magazine. It was the Department’s magazine. Like it was the Department’s computer or the Department’s fish tank. But to be honest, at some point that nonsense stopped, and I started thinking of it as mine.

I love this magazine. I love it because it lets people read about who we are and what we do. It gives the Department a vehicle to shout out how wonderful this state is and how the Department takes care of its wildlife and wild lands. It does it with compelling stories and with outstanding pictures, and it does it well enough to get noticed in state and national competitions amongst other magazines. Even better, it does it well enough to where subscribers tell me they’ve enjoyed it so much that they pass it on to a friend or family member.

Over the years, there have been special days that hold vivid memories. There was the day I joined a team of environmental scientists out of the regional office in Redding on a trek in the wilderness looking for something most people would avoid. These wildlife biologists had spent months tracking the first gray wolf that wandered into California since the 1920s. Designated OR-7, this wayward male split from his family in Oregon after they were captured and collared. The collar allowed wildlife experts to follow his travels as he roamed California. He ranged through the southern Cascades, across portions of the Modoc Plateau and then through the Lassen and Plumas national forests. He wandered as far south as Tehama, Shasta and Butte counties. Everything was fine until the collar unit failed and his whereabouts went up in smoke. That’s why there was the team heading out to find him, or at least find signs of his presence. They allowed me to join them and out of it came an Outdoor California feature on wolves returning to the state and the people who track them.

Another one of those days involved John Higley, a staple in the magazine. A veteran freelance writer, his articles on how to hunt or fish ran nearly every issue. Higley had a folksy manner of writing that was loose and easy. He wrote the way he spoke, and he loved giving people insight on how they can get the most out of their time in nature. He invited me to go fly-fishing a half dozen times before I was able. He lived outside Redding, and he took me above Burney Falls, where we moved upstream until he finally decided this was good enough. The spot was bordered by lush overgrowth and the only sound was the flowing water. I’ve never seen anyone handle a fly-fishing rod, reel and fly like Higley. He identified a pool of water where the current stalled, figured it was where trout would gather. He flipped his line a few times to get the fly exactly where he wanted, a few yards upriver, before allowing it to float down naturally and then hover just long enough… Gotcha! He showed me the technique and encouraged me through several attempts. I did just well enough to not embarrass myself.

I did better with a camera I’d brought along. I ended up with a nice shot of him fishing along the river. I recall that day fondly and wish I’d taken him up on his other offers to go fishing.

There were other days of course, lots of others. But in 2020, we were all introduced to a nightmare that lingers still. In a September/October issue, I offered a column and expressed my uneasiness with what was happening. I made a connection to the time I had gone through winter snowshoe training in the military and the feeling of being utterly lost. I wrote, “The worst part of all of that was the sense of being out of my element. That lost feeling must have branded itself somewhere in the back of my memory because it’s a feeling I recognize today, watching my community wandering out of its element under the threat of a pandemic we’ve named COVID-19. If we’re not careful, our world will be defined by words like separation and isolation.”

I think that’s exactly what happened. I know for the longest time, employees worked from their homes. Some still do. And I know that we lost a lot of family and a lot of friends. I know some died as soon as they were exposed to the virus, others are fighting from lingering ailments that came with their diagnosis. I can’t help but remember Higley for this as well. His surprise call one afternoon from a hospital in Redding, saying he was bored because the staff there wouldn’t let anyone visit. He thought he’d call out instead. We chatted for a while and laughed about things that were funny and then hung up because I had work to do, and he had a nurse coming in. And two days later he was gone. It’s times like this that I understand how vulnerable we are as people, no matter who we are. It makes me appreciate all the more what I have.

There are times when life is hard. Work or home, life will throw you some curves, fill your world with joys and hurts. It can be something as unfathomable as a change in policy that cuts a program or changes its direction. Decisions like that come from higher up in the food chain. Or it can be something like hearing the results from a test ordered by your doctor that stops your world. That sort of thing comes from even higher up the food chain. Important things get disassembled and need to be rearranged. I’m taking the time to do just that.

I’m older now and that urge to grab everything and get to the next level isn’t as strong as it once was. That must come with age. For a long time, I stopped looking in mirrors, found too many lines on the face that looked back. I wasn’t sure I recognized it anymore. But the lines don’t bother me anymore, they come from times when I’ve laughed and cried, souvenirs of the life I’ve lived. They are trails through my world, marking where I’ve been. I recognize them as just a steppingstone to take me to something new. My hope is that it’ll be something fun and something meaningful. I want to believe the older I get, the better I am. At this point in my life, I know when to give it my all and when to just not give a damn. For me, that’s a good place to be.

It’s time to hang it up. If I had an office, I’d go in one last time and clear out what memories are left than close the door and hang a sign that says, “Gone fishing.”