“A click; the room was darkened; and suddenly, on the screen above the Master’s head, there were the Penitentes of Acoma prostrating themselves before Our Lady, and wailing as John had heard them wail, confessing their sins before Jesus on the Cross, before the eagle image of Pookong. The young Etonians fairly shouted with laughter. Still wailing, the Penitentes rose to their feet, stripped off their upper garments and, with knotted whips, began to beat themselves, blow after blow. Redoubled, the laughter drowned even the amplified record of their groans.”

“But why do they laugh?” asked the Savage in a pained bewilderment.

“Why?” The Provost turned towards him a still broadly grinning face. “Why? But because it’s so extraordinarily funny.” (11.54-6)

Huxley, A Brave New World

http://www.shmoop.com/brave-new-world/spirituality-quotes-4.html

Traveling the back roads of New Mexico can be disorienting. The Old Pecos Trail and the Old Santa Fe Trail may pass through the outskirts of Santa Fe, but before I know it, the narrow roads can suddenly turn off to a dirt road winding through six-foot high walls of tumbleweeds, sagebrush and mesquite. I am lost! I punch in Google Maps in the I phone, my campground destination, and the calming, confident female voice guides me back to home base. Amazing.

However, in two recent journeys to El Santuario del Chimayo, as country roads wind through Indian pueblos and old Hispano villages, I come to a cross roads with no directional signs and my digital guide through unfamiliar territory goes blank. The phone works, but no voice and the map on the phone makes no sense. As I look back now, I understand. I have entered mystical spiritual territory where I must carefully feel my way intuitively toward my destination. God give me a sign!

On Highway 76 (The High Road to Taos), we are driving north of Santa Fe through the Carson National Forest. On this warm spring day the dry, thin air is fragrant with the scent of pinyon pine and juniper. There is a village ahead, Las Trampas, and we turn off for a rest stop at La Casita Café. Warm frybread coated with cinnamon and sugar compliment spicy pinyon coffee. I am listening to conversations around us: English mixed with Spanish. I am fluent in Spanish and have a challenging time understanding until I catch some antique phases that remind me of the “thee” and “thou” in the old Episcopal Spanish prayer book. Now I understand. Local people are speaking in an 18th century Spanish colonial dialect, vestiges of four hundred years of Hispano occupation in these isolated New Mexican villages. As we pass the Church of San Jose de Gracia, I see an obscure square adobe building next door which I later found out is a morada sanctuary for the Penitentes or Brothers of Light.

We travel on looking for some direction toward Chimayo, but some unseen power has again disabled the GPS. We pass through Las Truchas. I recognize the market and other buildings from my favorite film by Robert Redford, The Milagro Beanfield Wars (1987).” When I play music from the film soundtrack, it captures the spiritual powers in this place, where villagers regularly consult with santos and angels in their daily life.

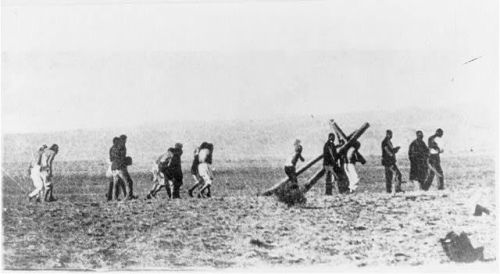

God give us a sign! And there it is! At this midpoint in the holy season of Lent, I can see just ahead of me four men walking together, barefoot, following a bearded young man, jet black hair flowing freely to his waist, carrying the heavy beam of a huge wooden cross. Penitentes are walking toward Chimayo. I should get out and walk behind them to find my way. Just then I hear bells. Church bells. It is noon. The 11am mass has just ended. I must be near my destination.

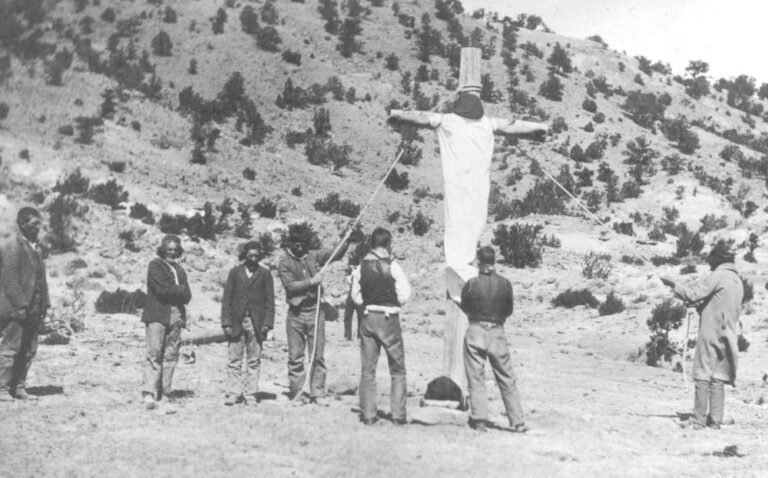

Students of cultural anthropology will have studied the penitents of New Mexico, Los Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno (the Brothers of the Pious Fraternity of Our Father Jesus the Nazarene). Popular media through the years have observed the strange rituals of flagellation and crucifixions. The 1937 film “Lash of the Penitentes”, which is mocked by the Etonian students in Brave New World, derides the primitive rituals as “horrible” and “abusive”.

Perhaps some of the best photographs of the Penitentes in New Mexico were taken by Charles Lummis. In his book, The Land of Poco Tiempo, Lummis wrote

“so late as 1891 a procession of flagellants took place within the limits of the United States. A procession in which voters of this Republic shredded their naked back with savage whips, staggered beneath huge crosses, and hugged the maddening needles of the cactus”. (p. 56).

Ironically, Lummis fostered trust in order to photograph these private rituals in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and used his images to feed an insensitive, critical Anglo press which fostered a sensational stereotype of the Penitentes.

The curious rituals attracted many spiritual seekers. However, they belittled the primal practices of the Brotherhood. Visitors to New Mexico were enchanted by the Hispano-pueblo culture. But when they reported back about their experiences with these local spiritual rituals, it seemed to come from a disconnected realm of reality.

Pulido shares:

“What is critical to remember is that Lummis’s work would establish the framework for the hundreds of popular and scholarly publications that, like his own work, ignored the importance of penitente understanding and thinking about the sacared in their lives.”

P 37 The Sacred World of the Pentitentes.

However, the procession of the cross which I witnessed on the side of the road is a vestige of a profound spirituality deeply imbedded within the hearts of the people who live in the pueblos which dot the lands around Sanctuario del Chimayo.

The roots of the ascetical practice of flagellation go back more than a thousand years to Spain and Italy, identifying with the Flagellation of Jesus during his Passion. Ascetical practices were a very early part of Christian spirituality. The Protestant Reformer Martin Luther, as a Roman Catholic monk in Erfurt, Germany, had a whip hanging on the door of his cell for regular mortification. The Roman Catholic Church suppressed the practices in the 14th century, but as we will see, the Church cannot put a damper on popular piety.

The Spanish ascetical traditions came to New Mexico. After Mexican Independence in 1821, the Church replaced the Franciscan, Jesuit and Dominican missionaries with Diocesan priests. But as today in Mexico, there were not enough priests to go around, and little villages, like the ones around Chimayo, might only see a priest once a year.

Marta Weigle reflects:

“(a) century or more of improvisation in religious expressions, necessitated by the lack of ecclesiastics to minister in time of need, and to celebrate the important events of the Christian year, may well have resulted in a varied conglomeration of lay practices, prayers, penances and procession.” (Weigle 1976: 51).

Thus, the Penitentes filled this spiritual vacuum.

But the spirituality of the people is still vibrant. The men of these villages banded together for mutual support and community charity. Walking in the way of Jesus in his Passion on the Cross led these men to gather in moradas, enclosed adobe meeting houses. Is this a connection to Indian kivas? The village would know when the men were worshipping by the vibrant sound of their alabados songs. Their piety peaked during Lent and Holy Week with private flagellation rituals in the moradas and public processions of the cross.

The institutional church historically seems to have been very nervous about mystical experiences and this kind of popular piety. Archbishops Lamy and Salpointe tried to suppress these ascetical practices in the 19th century during the “Americanization” of the Church. The public rituals of penance and flagellation threatened traditional Catholic orthodoxy. As you would expect, this drove the brotherhood underground, becoming a secret society. There was a breakthrough in 1947, when Archbishop Bryne opened a new relationship with the brotherhood.

However, Enlightenment culture, which had pushed spiritual experiences off to the backroom closet in the assertion of human Reason, still had a fascination with this kind of popular spirituality.

Today at Santuario del Chimayo I could sense the powerful presence of the brotherhood and its continuing influence in villages of the Upper Grand Valley.

Jeffrey S. Smith writes:

“Not only have the Penitentes been the spiritual leaders of the community, but throughout the year they have provided services that might otherwise have gone undone. They have cared for the sick and poor, interred the deceased, organized wakes and rosaries at funerals, assisted the widowed, and administered the law and order within the village”

- 73.

From the early history of the Christian Church, these actions describe the ministry of the Order of the Deacons.

Alberto Lopez Pulido offers a deeper understanding of the brotherhood in The Sacred World of the Penitentes. He brings the reader to the inner heart of this spirituality, which includes care for those in need, prayer and meditation, and modeling Christ-like behavior. Pulido shares the personal stories of members of the brotherhood, whose familiar roots go back many generations.

Pulido contends that writers and historians, in their insensitivity to things spiritual, have undermined the primal place that the Penitentes have had in popular piety. As he shares personal testimonies from members, his book reveals the passionate Christian spirituality which infuses their rituals.

In Carl N. Taylor’s Agony in Mexico (1936), we find an example of a negative narrative. He witnesses the brotherly solidarity of this spiritual movement within the life of the Hispano pueblos in the area. But he was upset by the flagellation and crucifixion rituals. This reinforced Euro American negative stereotypes about the Penitentes.

The “canary in the gold mine”, is a metaphor coming from the California goldfields that relates to social injustice. The miners of ’49, as they dug tunnels deep into the Sierra Nevada, carried little bamboo cages holding live yellow canaries. Because the moist interiors of the mine tunnels often exposed poisonous gases, the canary in the cage was a first sign of danger. Dead canary, run for your life!

In the prophetic tradition of the Jewish scriptures, how the community cares for the widow, orphan and sojourner was the “canary in the gold mine” for the People of God. Oppression of the poor and vulnerable would bring God’s punitive judgment.

The Brotherhood of the Penitents inherit this Biblical consciousness in their attentive care for those in need in the community. This is a core value for them, “an act of charity.”

Walk with me as we follow a procession on Good Friday evening, moving slowly on the city sidewalk in downtown Santa Ana, California. We wait at the signal for dense homebound auto traffic to stop and we follow the direction of the police officers as we cross the street. Latino mothers, wearing dark head covering, gather little children hand in hand as a nurturing mother hen gathers her chicks. The sudden rain shower from an hour ago has cleared. Wispy steam rises from the street. Thunder in the distance is the last sound from the departing spring storm.

As you gaze ahead to the start of the long procession, you see a long-haired man bent over, carrying a heavy, huge wooden cross. The crowd beings to sing

Perdona tu pueblo senior

The procession stops at the front door of the University of California Clinic. A short step ladder is set up. A woman climbs with assistance and begins to read one of the Stations of the Cross. At the end of the mediation she offers her own prayer: for those incarcerated at the Orange County Jail near by and for her own son, who has been there for the past month.

The Procession of the cross, Via Crucis, proceeds, winding through the busy streets, singing penitential songs on this Good Friday Night, praying the fourteen Stations of the Cross. Men and Women alternate, carrying the heavy burden of this cross.

As you imagine this scene, how do you think it would be received if it were passing through the main street of your home town today? Surprisingly, as the procession carefully walks through the dense streets of downtown, families out shopping or going to dinner, pull aside from the sidewalk, and reverence the procession by removing hats and making the sign of the cross. This Good Friday Procession with a large, heavy cross reminds these Latinos of their hometown pueblos, where the same procession could be happening on this night. Some of these observers interrupt their evening plans and join the procession as it winds its way back to my parish.

In this Via Crucis, participants walk with Jesus in his passion toward the cross and crucifixion. This was a spiritual practice spread throughout the Western world by the Franciscans.