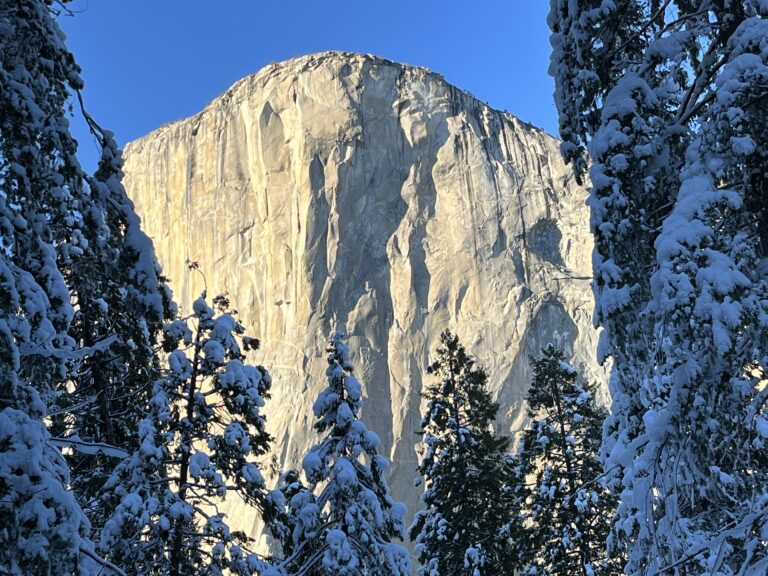

Granite cracks fill the dreams of rock climbers, and nowhere do they find better ones than Yosemite National Park. Climbers yearn to jam their hands and feet into them as they ascend towering walls, and none more attractive than El Capitan. Of course, if the cracks are too tight to securely grip, or if protection like bolts and pitons are unavailable, then long falls are possible, sometimes 100 feet or more.

A good pendulum swing makes hearts pound, too. Faced with steep and featureless rock, climbers anchor their rope to bolts, descend to the rope’s ends and run back and forth, “swinging like yoyos,” to reach distant ledges.

Climbers Errett Allen and Mike Corbett braved these hazards while climbing the famed El Capitan. Then a December surprise kicked their adventure into another gear.

An icy rainstorm soaked the climbers and halted progress on their fourth day. By the time they hastily set up a hanging shelter, they were drenched and nearly hypothermic.

Worse yet, “we discovered that all of our bivvy gear was soaking wet! We had been careless about packing it that morning,” recalled Allen. The men wrung out their wool clothes, put them on and rubbed their numb hands and feet for warmth.

As the sun set and temperature dropped even more, they found their sleeping bags and jackets were no longer wet. “They were now frozen lumps of ice, completely useless,” Allen said. “That night was the longest and coldest bivouac of my life… Sleep was impossible.”

Climbing El Cap fulfills the lifelong dreams of many; triumphant shouts echo from the mountaintop often during the climbing season. But not everyone who attempts the 3,000-foot granite monolith succeeds, and some who do reach the coveted summit grapple with mountain-sized adversity along the way.

Allen and Corbett faced more difficulty than most when they attempted a route called New Dawn. The two had years of experience, 200 pounds of gear and a sunny forecast but still had to fight for their lives. Frigid rain was just the beginning as snow arrived on the sixth day, immobilizing them again.

Because their pendulum traverses delivered them to an overhanging part of the mountain, “retreat was completely impractical.” They could not simply rappel to the ground because their rope could not reach that far; the line would end in mid-air.

Friends shouted encouragement from El Capitan Meadow below and offered to get help. More than a few would have accepted, but Allen and Corbett declined. “We shouted back that we were okay and didn’t want a rescue,” Allen said.

Weather cleared on the seventh day, raising the climbers’ spirits. Then hope turned to terror as sunshine loosened ice above which crashed down around them. “Blocks of ice two to four feet thick and as long and wide as railroad boxcars began to peel off the rim. They would flip over and over like playing cards, making an incredibly loud and dreadful whoosh with each flip… They smashed into the wall with great force breaking into thousands of pieces which showered the forest below,” Allen said.

Finally, they pulled themselves onto the summit on their eighth day. “Though tired, sore, hungry and weak, we were completely elated at having survived and accomplished our goal through so much adversity,” Allen said. Few El Cap climbers have achieved a harder-won victory. All that remained was a final night in the freezing elements and an eight-mile descent hike through deep snow.

El Cap has a way of dealing out unexpected challenges, as countless climbers will attest.

In 1958, Warren Harding led a team which labored 47 days to achieve the first ascent of El Cap’s sheer face. A final push through a cold night brought the exhausted group to the summit on Nov. 12. “El Capitan Conquered,” cheered one newspaper, though Harding himself was more modest: “It was not at all clear to me who was conqueror and who was conquered… El Cap seemed to be in much better condition than I was.” The pioneers named their new route The Nose, as it divides the mountain’s wide face vertically down the middle.

That breakthrough changed climbing forever. Through the 1960s, climbers flocked to Yosemite to establish new routes. Meanwhile, El Cap witnessed its first long falls, though the use of ropes, pitons and other equipment usually prevented injuries.

Some climbers focused on speed. In 1975, three climbers summited in just 15 hours, the first ascent in less than a day.

Up to this point, big wall climbing involved pitons and what climbers call direct aid, which means pulling and standing on gear to assist in upward progress. Then free climbing, in which climbers scale just the rock and use gear only to protect falls, came into vogue even on large objectives. Two climbers made El Cap’s first free ascent in 1988.

Yet with these achievements came great loss. According to a Yosemite study of climbing from 1970 to 1990, 51 climbers died from traumatic injuries and four perished from hypothermia in those years. At least 57 more would have perished without fast help from Yosemite Search and Rescue. More than 100 accidents caused at least 50 broken bones and a far greater number of sprains, cuts and bruises annually during that period.

By the 1990s, climbers were combining speed and free climbing, and ascended El Cap both in a day and free. The Nose became ever more popular, as ascents increased from one every few years to multiple parties per day. The route’s excellent rock quality, scenery, ease of approach and historic significance make it perhaps the most coveted climb in the world.

Among the climbers who felt its pull are Noah Kaufman and Bernard Guest.

“When I first arrived in the valley, my jaw dropped to my knees. I didn’t know anything like that could exist in the world. It was way more impressive than anything I had seen up to that point in my life,” Kaufman said.

Finding El Capitan especially magnetic, Kaufman and Bernard set their sights on The Nose. A third climber also named Noah offered to join their team; he claimed to be an expert who had climbed the wall before. “Perfect!” Kaufman thought.

Like most groups, the three planned a multi-day effort and brought food, water and overnight gear in a haul bag, which climbers call a pig. By this era, climbers had mostly abandoned pitons, which mar rock over time. Instead, they placed less damaging forms of gear, like spring-loaded cams, in cracks for protection.

“We had a really fun day climbing the Stoveleg Cracks,” Kaufman said, referring to a popular section. “We were leapfrogging and taking turns leading. I learned how to jumar (to ascend a fixed rope) and the three of us were getting our systems down… The climbing was immaculate and world-class.”

As the wall steepened, the team’s supposedly most-capable member seemed to falter. About halfway up the wall at a spot called Eagle Ledge, Noah began a moderate lead, protected himself with a cam in a crack, but seemed “scared and intimidated,” Kaufman said.

Then Noah fell. That should not have been a problem, as he was roped. But while leading, he scraped the rope against a sharp edge. His fall weighted the line against the knife-like granite and instantly broke it. For a heartbeat, Noah plunged toward seemingly certain doom. However, against all odds, he landed beside his teammates on tiny Eagle Ledge, just one foot wide, uninjured and even unaware of his nearly-impossible luck.

Kaufman, horrified, immediately secured his partner with a sling and carabiner. “We had this long moment of silence while we all visualized him falling a thousand feet and becoming a ketchup smear on the slabs below,” Kaufman said. “Noah’s shirt was off and I could see his heart pounding as he put it together. Then he knelt at the belay and started sobbing… I think it was a miracle if ever I saw one.”

Though Noah wanted to descend, the team regrouped and continued, overcoming more typical challenges. These included running low on food and water, dropping gear, and hauling “the pig” through obstacles like rock constrictions called chimneys. Finally they reached the summit.

“We were psyched when we got up there. We took pictures and gave high-fives. It was definitely a bonding experience,” Kaufman said. After descending, “we went straight to eat and spent all the little money we had on a carpe diem, mega dinner. This experience was an exciting story to tell in the dining room though there were some climbers who never believed it. People began calling me ‘Catching Noah’ and him ‘Falling Noah.’”

Traumatic as it was, the ordeal gave Kaufman more confidence and self-reliance. “That first big wall was the ultimate trial by fire for me, and I thought I’d never do another one, ever. The Nose was the most crazy, horrible, amazing, and way-too-intense experience I’d ever had. But of course I went back and I’ve done a bunch of big walls since. Now that I know what I’m doing, they’re a lot more fun.”

Achievement and danger both seemed to magnify in the last decade.

Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson labored seven years to free climb El Cap’s absurdly-difficult Dawn Wall. The route’s crux (hardest section) is a horizontal traverse across rock with only the tiniest holds for fingers and toes, spaced far apart and sharp enough to draw blood when gripped. Caldwell and Jorgeson practiced this 15th pitch (a section of climbing about the length of one rope) hundreds of times before succeeding. The men’s final push up Dawn Wall triumphed over 19 days in 2015, drawing international attention and even a White House shout-out from President Obama.

That was a tough act to follow, but in 2017, Alex Honnold answered with an even more unthinkable feat: El Capitan’s first and only free solo ascent. After years of preparation, he climbed the Freerider route without a partner, rope or any protective gear. Honnold’s self-imposed challenge required him to climb perfectly or die, caused his girlfriend to break into tears, and astonished the world.

Those jaw-dropping exploits became commonly known through the beautifully filmed “Dawn Wall” and “Free Solo” movies. By spending nearly as much time on the wall as the climbers, filmmakers gave the general public its best look ever at big wall life. Climbing’s popularity grew even greater.

For an encore, Caldwell and Honnold teamed up in 2018 to shatter The Nose speed record, sprinting up in a mind-boggling 1 hour and 58 minutes. Typically, climbers work in pairs and one leads while the other remains anchored to manage the rope. But speed climbers ascend simultaneously, greatly increasing both their pace and danger. If either partner falls, the rope will probably pull the other down also, and their plunge may be long before their gear stops them, if it does. Caldwell and Honnold did not fall, and together set a record that may stand for a very long time.

Increased interest in climbing and the dangerous techniques climbers adopted brought a rash of serious accidents. Since 2000, a dozen fatalities occurred on El Cap alone. An especially bad year was 2018, when one climber broke both legs, another broke her spine and two more fell to their deaths. All four were highly experienced, with hundreds of El Cap ascents between them.

Some sustain injuries or worse through risks which threaten anyone even near the steep mountain. A party dropped a haul bag in 2016, breaking the arm of a climber below. Rockfall, described as “the size of an apartment building,” killed a climber and injured another in 2017. A fist-sized rock hit a climber sleeping in a hammock in 2021, fracturing his skull.

However, a large majority of climbers either ascend, or sometimes retreat, safely. Yosemite estimates 25,000 to 50,000 climber days annually, resulting in about 100 accidents and 15-25 rescues per year. That would mean that more than 99 percent of climbs end without problems.

“Most climbers do a good job coping with the hazards of their sport,” wrote ranger John Dill, a search and rescue veteran with more than 40 years of experience, in a well-read cautionary report called “Staying Alive.”

Yet, 121 climbers died in the park since 1905, including 32 on El Capitan.

All but five fatalities occurred since Harding’s team pioneered The Nose in 1958. Most El Cap accidents occur on the easier sections where climbers may be overconfident.

Climbers could and should reduce the accident rate, Dill wrote, by anticipating and preparing for the multiple dangers they could face. Wearing helmets, bringing enough water, carrying rain gear, studying descent routes, rappelling properly, and placing protective gear even on “easy” terrain are a few of his suggestions.

“At least 80 percent of the fatalities and many injuries were easily preventable. In case after case, ignorance, a casual attitude, and/or some form of distraction proved to be the most dangerous aspects of the sport,” Dill wrote. “Climbing will always be risky. It should be clear, however, that a reduced accident rate is possible without seriously restricting the sport.”

Cathie Yun and Julie Wang, who climbed The Nose in 2022, seemed to embrace the planning and caution that Dill endorses. Before their attempt, they improved their fitness and skills with months of training and practice runs on the wall’s bottom half. Then they scheduled their adventure for June, when favorable weather was likely. “We are team ‘safety first,’” Yun said.

Wang declared the Stoveleg Cracks “the best pitches ever.” Completing the King Swing maneuver (a wild pendulum traverse) led to “whoops and delight.” One by one, the pair negotiated well-known challenges like the Great Roof and Changing Corners pitches. They spent their nights comfortably on ledges, dining on pad thai and making video calls to friends. A few miscues, like a short fall, a dropped phone and “rope shenanigans,” caused no serious problems as they summitted in four days.

Supporters welcomed them at the top with hot stir fry, pineapple and champagne. “We feasted, we hugged, and we were so so happy, feeling all the feelings,” Yun recalled.

Avoiding the near-death epics of the Allen and Kaufman parties, Yun and Wang enjoyed “the experience of a lifetime.” Perhaps their successful adventure best illustrates why people don’t just dream of climbing El Cap, and risk their necks trying, but actually enjoy it when they do.

El Cap has provided the author some memorable moments, though I have less experience on the mountain than the others named in this article. After discovering Yosemite climbing in 1994, I enjoyed several short and moderate routes on the mountain’s base like Little John, La Cosita, and Moby Dick.

Naturally, I felt the mountain’s pull to climb higher, and the obvious place to start is on its easiest route. The East Buttress leads up 1,400 feet from the top of the large talus slope. Though it presents little difficulty to advanced climbers, the route was quite challenging for me. The first time I attempted it, I fell near the bottom and landed on a piece of gear, leaving a bruise on my hip that reminded me of my error for weeks.

Later I tried again with an English partner who I met in the climbers’ mecca of Camp 4. We hiked to the base in darkness and roped up at dawn. This time I climbed better on the chimney where I fell before. The third pitch provided the crux, ten feet of nearly featureless granite which climbers must ascend on toes and fingertips. Also memorable was a traverse high on the route which, though easier, risks a heart-stopping pendulum swing thousands of feet above the valley floor. We traded leads on a perfect summer day. Finishing that route felt great, demanded a celebration of pizza and beer in Curry Village and marked a highlight of my modest climbing career.

Part of me wants to climb something bigger, and though I’m now in my early 50s, I haven’t ruled it out. I’m not put off by the danger, even if I should be, which I regard as significant but acceptable.

In that regard, I seem to be in good company. Record-breaking climbers like Hans Florine and Emily Harrington both recovered from El Cap injuries and returned to climb the mountain again in recent years.

Another who bounced back is Becca Skinner, niece of free climbing pioneer Todd Skinner, who died in a 2006 rappelling accident. “I swore I would never climb again. However, six months after the accident, I was drawn back to the rocks,” she recalled. “Climbing will always be a part of who I am. It’s rooted in the depths of my soul.”

If even those who experienced injuries and lost loved ones keep climbing, those who haven’t suffered such losses seem even less likely to turn away.

Among hundreds who summited El Capitan in 2022, a father and son duo gained the most attention. The pair relied on two guides to lead a four-day climb and anchor ropes which the Bakers ascended with jumars. Sam Baker, the eight-year-old son, became the youngest climber yet to ascend ropes up Yosemite’s signature mountain. Father Joe Baker gushed with pride on social media and multiple news outlets.

Some members of the climbing community criticized the decision to expose a child to such danger. Yet the elated Bakers seemed unmoved.

“It feels like we’re above eternity up here,” said Joe.

“It was awesome and I’m the youngest to do it,” said Sam. “In a few years, I’m going to come back and free climb it.”