The sonorous tone of mission bells announced arriving travelers along California’s El Camino Real from 1769 to 1834. Increasingly today, the jingle of bicycle bells announce the arrival of cyclists at the 21 Spanish missions beside this Royal Road.

Touring the California Mission Trail by cycling or hiking is an “epic adventure” says Sandy Brown who wrote “Hiking and Cycling The California Missions Trail” (Cicerone, © 2022). Brown pedaled and trod the 800 mi/1,287 km trail eight times while researching his guidebook.

Highway US 101 follows much of the original trail, though it is possible to bike or hike on lightly traveled roads along the route past rich agricultural fields, over rolling hills of golden grass and dark green oaks, and beside one of the most scenic coastlines on Earth.

Brown says, “The story of America” is experienced by traveling the route. It is about Stone Age civilizations suddenly overwhelmed by technology, science, and religion; about an expansionist continent and an innocent one colliding head-on.

This all happened in a span of a hundred years, starting in 1769 when Franciscan padre Junípero Serra arrived and began building missions. A century later the transcontinental railroad was completed, sealing the fate of the untamed west. What evolved in California during that time took three centuries in the rest of the country.

Spain’s King Charles III established California’s missions to discourage Russia and England from establishing a presence in Alta (upper) California which might threaten Spain’s hold on Mexico. His strategy was two-fold: establish military outposts (presidios) and build nearby communities (pueblos) populated by Indians who would become loyal to Spain.

Because the missions were at the bitter end of a long and fragile supply line, Franciscan priests built communities using newly converted natives unfamiliar with construction or ranching.

California’s first mission in San Diego nearly failed, as critically needed supplies did not arrive until the settlement was about to collapse. Considering the obstacles, it is remarkable that the 21 missions eventually created remain so beautiful today.

The first structure built at each mission was its church. It was made of broad, sun-dried adobe bricks (mud and straw), plastered with crushed white limestone and seashells (to keep the adobe from dissolving in the rain) and roofed at first with thatch, then with baked clay tiles to prevent wildfire damage.

Mission walls were thick. Few doors or windows were added, as they weakened the structure. Rooms were dark with illumination coming from candles.

Churches were limited in width to the length of the tallest local timber. So, they were uniformly narrow. Interior walls were colorfully painted with Indian designs or faux marble patterns mimicking the grand interiors of European cathedrals. Lacking glass, clerestory windows (set high on the walls to discourage theft) were covered with paper-thin rawhide through which a dim, golden glow lit the interior.

A statue of the mission’s namesake – usually a saint or sacred day – would appear prominently above the altar. Interior paintings and statues helped illustrate the complex religious concepts to native people. To communicate the importance of baptism, the baptismal font was given a prominent position.

Attached to the church was a quadrangle containing a broad patio where mission residents would congregate, animals were stabled and festivals were held. Most quadrangles housed quarters for priests and monjerios for maidens, a dormitory for men, barracks for a few soldiers. Workshops for cooking, (tanning and candle-making were nearby.

A shaded walkway (corredor) ringed the inside of the square where, during fiestas, resident Indians raced roosters, demonstrated their equestrian skill and held California-styled bull fights in which the bull wasn’t killed.

Each mission had a bell tower Bells announced the start of church services, the approach of travelers and the threat of imminent danger. Surrounding the mission, cultivated fields and pastures extended for miles.

Today, most of the missions have been restored and remain active Roman Catholic churches. Other structures are repurposed as museums. Unfortunately, little of the sprawling pasture lands remain.

Many mission walks begin in San Diego and travel north. However, because prevailing winds blow from the north, it is easier for a cyclist to ride south. This journey began 75 mi/119 km south of San Francisco at La Misión de la Exaltación de la Santa Cruz (Mission of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross) and traveled just 323 miles south to Mission La Purísima Concepción near Lompoc.

Mission Santa Cruz was the 12th mission in California established by Franciscan priests (1791). Like all of California’s missions, the original mission buildings and church eroded. In this case, they were destroyed by an 1840 earthquake. Catty-corner to where it once stood, a 1/3-scale replica of the original mission church was erected in 1931. The replica serves double duty, as a chapel for church weddings and baptisms and as a California State Historic Park with exhibits that tell the story of native Ohlone and Yokuts people.

Not all missions are open daily. Mission Santa Cruz is open Thurs. – Mon. Before riding the distance to see a mission, always check its operating schedule. Inside, the Latin text of Adoramus te – the stanza recited or sung repetitively during the stations of the cross – arcs above the church sanctuary, referencing the mission’s namesake … the Holy Cross.

Worship is the reason most visitors come to Santa Cruz … sun worship. Its south-facing, sandy beaches are revered destinations for residents of the San Francisco Bay Area. So too, is Santa Cruz’s surf.

Surfing started here in 1885 and was an occasional local oddity until 1927 when the city was originally described as Surf City. In 1952, local surfer Jack O’Neill created neoprene wet suits allowing him to surf off the chilly California coast. The added insulation allowed surfing to evolve into a global sport.

Steamer Lane is a popular break near Lighthouse Point. Here surfers in wet suits ride the waves. There’s a Santa Cruz Surfing Museum and the O’Neill Shop that sells Surf City souvenirs. Do not miss the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. Stroll out onto the wharf for views of beach volleyball, lounging sea lions and the scream-inducing roller coasters of the oceanside amusement park nearby.

Picturesque views of Monterey Bay continue along much of the 39 miles between Mission Santa Cruz and Mission San Juan Bautista. Capitola, Aptos and Manresa State Beach are prime viewpoints before heading inland along the gravelly Aromas and Anzar roads, over the oak-speckled Gabilan Range to San Juan Bautista. (For specifics on the route refer to a guidebook or get cycling directions from Google Maps.)

As you pedal east (est. 3.5 hrs, nonstop), the “rocky Gabilan mountains” bring the writing of novelist John Steinbeck to mind. The area hasn’t changed much since Lennie and George traveled them in Of Mice and Men.

Descending into the San Benito Valley, one is struck by the bold squares of tilled dark soil and rows of green crops lying over California’s infamous San Andreas Fault. This was the epicenter of the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 which in addition to destroying the city, 91 mi/146 km to the north also leveled Mission San Juan Bautista. The mission was reconstructed and survives as an active church with an unbroken succession of pastors since its founding in 1797.

There are 49 historic sites within San Juan Bautista State Historic Park and National Historic District including the Plaza Hotel, originally erected in 1814 as a barracks for Spanish soldiers. A two-mile Historic Walking Trail includes all 49 sites, including the town’s impossibly tiny calabozo (jail) which was used for 70 years.

La Misión del Glorioso Precursor de Jesu Cristro, Nuestro Señor San Juan Bautista (Mission of the Glorious Precursor of Jesus Christ, Our Lord Saint John the Baptist) was the 15th and largest mission. It borders the only original Spanish Plaza remaining in California. Although rebuilt following the 1906 earthquake, the mission church and its quadrangle need further restoration, as evidenced by the tree sprouting from its campanario. Yet inside, Mission San Juan Bautista remains glorious.

Illuminated statues of saints glow in six alcoves behind the altar. Frescos of oak leaf garlands, flowers, and faux Roman columns adorn church walls. The mottled yellow walls of nearby chapels almost seem to dance in the light of devotional candles. Outside, a bronze statue of St. John the Baptist lifts his arms in veneration of the new day.

There is a common misunderstanding among Californians that the missions were established a day’s walk from one another. That was not intended. Initially, the missions were placed at points of greatest military strategic importance (e.g., San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, San Francisco). The second wave of missions went where large native populations lived (e.g., San Antonio, San Gabriel, San Luis Obispo). This led the missions to be established at random points up and down the state, mostly near the coast to deter the threat of invasion by other European powers. Eventually, thought was given to providing stopping points between the larger missions making the interval between the missions about a day’s walk apart.

About ten California Mission Walkers complete the 800-mile trek each year, though hundreds of walkers are trekking between missions at any time. Mission walker Jerry Edwards says those traveling the California Mission Trail do so individually or in small groups. They hike or cycle for the physical challenge, to experience natural California as the Spanish explorers did, or to make a spiritual pilgrimage in the footsteps of St. Junipero Serra.

The 41.4 mi (67 km) route from Mission San Juan Bautista to Mission Carmel (est. 4.2 hrs) is arguably the most beautiful section to be ridden or walked between California’s missions. It climbs back into the Gabilan Mountains crossing by way of a section of the old DeAnza trail (the original route taken by the first Spanish expedition). It eventually was a stagecoach route between San Juan Bautista and Monterey. At points, it winds beneath canopies of ancient, twisted oak and California sycamore past ranch and farmlands that haven’t changed much in 200 years. It is the closest you will experience to seeing untouched California as it was in the late 1700s.

Since the trail varies from pavement to dirt and gravel roads, the best choice is a hybrid bike with a wider tire, as road bikes would be awkward to balance on dirt or gravel. “Biking,” says Brown, “solves the problem of distances that are hard to walk.” Road surfaces are generally good, though decaying, uneven, and fractured pavement is found in rural areas of the trail.

Continuing past fields of strawberries, lettuce and artichokes, you eventually reach Monterey Bay, then ride past historic Monterey, the original capital of Spanish California, through Cannery Row, made famous by John Steinbeck and renowned for its Monterey Bay Aquarium and many shops and restaurants before continuing along the sweetly seaweed-scented coastline along the scenic 17-mile Drive past the golf courses, forests of windswept Monterey cypress trees and opulent $10 million mansions of Pebble Beach, to the peaceful hiss of crashing surf, the staccato bark of sea lions and the urgent call of seagulls.

Pebble Beach Visitor Center colorfully reveals the history of this storied place and the athletes who won golf championships. There’s so much to see it warrants an extended stay on the Monterey Peninsula. Mission Carmel is a short climb through the storybook artists’ community of Carmel by the Sea.

La Misión San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo (Mission San Carlos Borromeo of Carmel) was California’s second mission (1770). It was one of nine missions founded by the father of the California missions, Saint Junípero Serra and his favorite.

Canonized as a Saint of the Catholic Church by Pope Francis in 2015, Junípero Serra’s lifelong ambition was to be a missionary. His motto was “siempre adelante” (keep moving forward), which he lived resolutely, despite personal hardships, illness, and painful suffering. He was a complex, driven man who is today, both venerated and criticized for what he did.

Junípero Serra was a product of his age and his beliefs. He sought to bring his faith to the natives, convert them, teach them modern agriculture and manufacturing, and protect them from the predations of soldiers and authorities. However, his efforts both succeeded spectacularly and failed miserably.

Spain’s King Charles had outlawed the enslavement of native people, but the mission fathers did not allow baptized Indians to leave other than for brief visits with family. This was done because should an Indian return to his former life, he was viewed by the mission priests as renouncing his baptism and thus dooming his soul in the hereafter. The padres were attempting to protect Indians from eternal punishment but ended up forcing them to stay at the missions.

Similarly, unwed girls were housed in monjerios to protect their chastity. However, these dormitories had few windows or doors. In the late 18th century, nothing was known about the transmission of diseases. So, smallpox and measles spread quickly, resulting in high mortality rates, all in the misguided effort to protect the honor of unmarried women.

The priests anguished over finding spiritual remedies. By the end of the mission period, 100,000 of 300,000 native people who once lived in California had died from diseases for which they had no immunity or treatments, and many centuries-old Indian cultures and languages were lost.

Some blame Junípero Serra, but what led to the decline of the Indian population happened largely after his death and a similar fate would have resulted due to other forces and events. In the first year of the California gold rush (1848), an estimated 120,000 native people died from being displaced and murdered by 300,000 gold seekers. Sadly, by 1900 the population of California Indians was just 16,000.

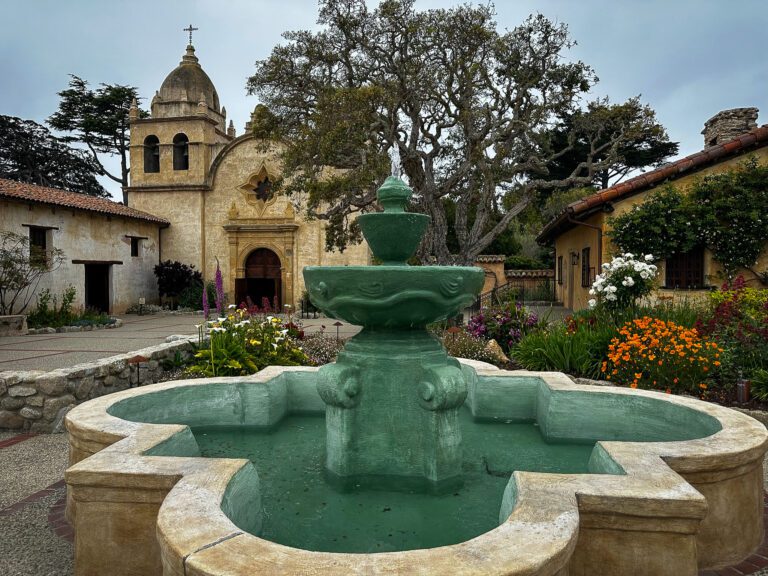

Carmel is the most beautiful of all the missions. Its domes, landscaped courtyards, star-shaped stained-glass windows, Spanish tile floors, a vaulted and arched church ceiling, verdigris fountains, displays of colorful mission artifacts and baroque Spanish decor combine simplicity with grandeur. Many of the church’s interior furnishings are original. A museum depicts life at the mission and St. Serra’s spartan quarters attest to his life of poverty and piety.

Brown believes Mission Carmel is “sort of the capital of the Serra cult… it romanticizes the mission period, with paintings of Serra at work and relics of his life, representing the high point of the romantic idea of what the mission fathers did.”

From Carmel, the Royal Road travels east toward Salinas, then south through the Salinas Valley. The area is called the Salad Bowl of the World because of its vibrant agricultural industry. The route hugs the foothills of the Santa Lucia Range, rising, twisting, and then dropping past verdant fields of lettuce, spinach, broccoli, strawberries and cauliflower. To the west, vineyards climb the hillsides, providing grapes for one of California’s largest American Viticultural Areas (AVAs), Monterey County.

After traveling 49.5 mi/79.6 km south from Carmel (est. 4.25 hrs) past springtime fields of orange California poppies, pink wooly buckwheat, creamy yarrow and yellow mustard seeded by the padres as a means of marking the route, you reach Mission Soledad. Plan on riding two hours more for lodging in King City.

La Misión de Maria Santísima, Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (Mission of Holy Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows) was the 13th mission established in California (1791). Perched in a parched part of California, it was named after an Indian woman whose name sounded like soledad, or loneliness. Today, it provides a rest stop for those cycling between Missions San Antonio and Carmel.

Soledad has experienced more than its share of sorrows. The mission’s proximity to the Salinas River caused it to be flooded in 1824, 1828 and 1832. Each inundation was devastating for structures made of mud and straw. In 1828, an epidemic killed many of its 628 Indian residents. Soon after, mission priest Fr. Francisco de Sarría died, causing most who remained to leave in despair.

Mission Soledad is one of the most modest along the trail. It’s simple white walls, gabled roof and lone mission bell speak to its austerity. Cyclist Richard Scholl said he found the mission to be “the most moving spiritually in its isolation and simplicity.”

When rebuilt in the 1950s, a chapel modeled after the original mission church and a wing representing part of the quadrangle created a sense of the original mission. There is a small museum and store. The adobe walls of the rest of the square are in ruins.

Inside the chapel, the mission’s patron saint, Our Lady of Sorrows, is dressed in mourning black and set in a niche surrounded by a depiction of the river of life, repeated in paintings and carvings and representing souls bobbing up and down. Its original stations of the cross (linen placards that mark the significant points of Jesus Christ’s capture, torture and execution) hang from the chapel’s walls.

Nina Solis is typical of visitors who come from nearby communities or pull off nearby U.S. 101 for a short stop. Solis drove to Soledad from Salinas with her children. “We don’t travel a lot. So, when I learned about the missions, I became fascinated by their story. We think we’re struggling now, but then we see what people had to deal with, how hard life was in the past.”

Though alone and afflicted, Mission Soledad was never completely abandoned. Shelters have been erected by area farmers and ranch families to protect the remaining original mission walls from melting away.

There is a quiet dignity and palpable sorrow at Mission Soledad, a survivor among survivors.![]()

In Part II of this article, Poimiroo’s journey continues to Missions San Antonio, San Miguel, San Luis Obispo and La Purisima. Advice on how to travel the route, where to stay and which attractions to visit will be included.